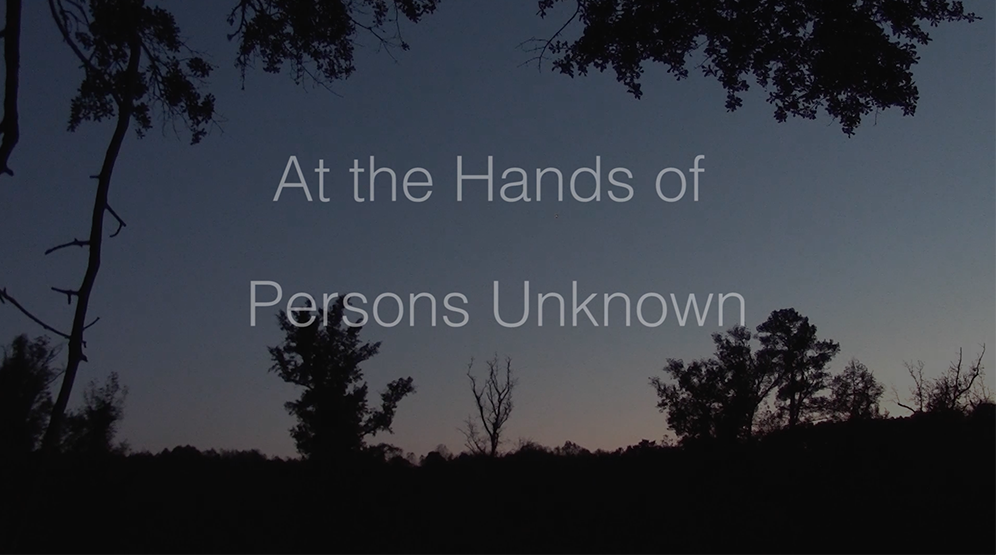

At the Hands of Persons Unknown

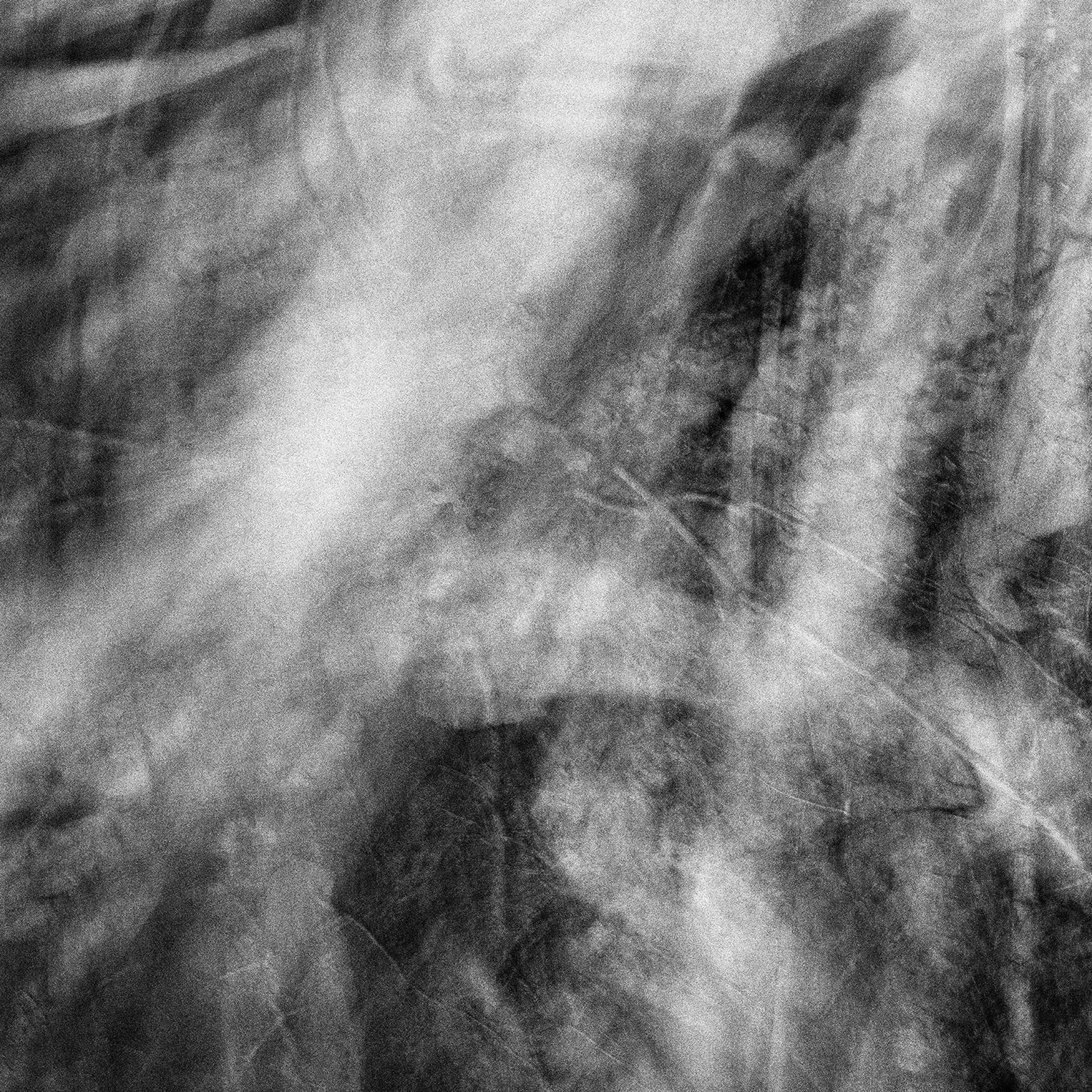

untitled 6 (2014)

At the Hands of Persons Unknown explores how trees have been silent witnesses to the lynchings of women in the United States.

I was motivated to create this series as a white German woman married to an African American man living in the American South, but from the perspective that if we had been born a generation earlier our relationship would have been illegal, if not cause to be lynched. The landmark U.S. Supreme Court ruling, Loving vs. Virginia, only ended the prohibition on interracial marriage in 1967.

Through long exposure and movement of the camera, the trees and the branches I captured were rendered abstract, almost ghostlike. And rather than photographing trees which were supposedly known to be used for lynchings (in most cases these trees no longer exist, as well as almost untenable to try to identify “lynching trees” with any certainty), I photographed old Southern trees as “stand-ins”. I made this decision after my mother-in-law first visited us in the South, when she said that she couldn’t look at an old Southern tree without imaging them as lynching trees.

2013-2015

Archival Pigment Prints

40 x 40”

Edition of 5, 1 AP

untitled 8 (2015)

untitled 2 (2013)

untitled 5 (2013)

untitled 3 (2014)

untitled 3 (2014) untitled 4 (2013)

untitled 4 (2013)Lynching has been one of the most odious aspects of mob violence in the United States since the nineteenth century. Although lynching’s roots can be found in the British Isles, and its use against blacks actually precedes the end of slavery, lynching emerged as one of the brutal tools of racial control to suppress black civil rights and to maintain white supremacy. By far, the majority of lynching victims were black men. However, a sizable minority were non-whites, poor whites, and women[1]. More than four thousand African Americans were lynched across twenty states between 1877 and 1950, and mostly in the American South[2]. For eight decades, from 1882 to 1968, the Tuskegee Institute recorded 3,446 lynchings of blacks, and 1,297 lynchings of whites.

But for a number of women, the majority occurring before the Great Depression, there were about 169 recorded lynching cases from 1837 to 1965. Of the 169 cases, Crystal N. Feimster cites in her 2009 book, Southern Horrors: Women and the Politics of Rape and Lynching, that eighty-three percent were black, sixteen percent white, and one percent Hispanic[3][4]. Eighty-three of the lynchings were carried out between 1837-1898, sixty-two of which were black, nineteen white, and two Mexican. In a correlated period between 1899-1965, eighty-seven women (seventy-nine black, eight white) were lynched. However, numerous more would have been raped, tarred, feathered, tortured, and mutilated.

untitled 12 (2015)

untitled 17 (2015)

untitled 11 (2015)

untitled 11 (2015)These lynchings highlight the violence of white male supremacy against black, white, and ‘other’ women, as well as black men, and the project exposes an often-overlooked aspect of U.S. history. Given the renewed interest into the many ways women are oppressed by contemporary power structures, exploring the forgotten history of female lynching is both timely and relevant to contemporary debates on notions of race, gender, and sexuality.

untitled 15 (2015)

untitled 15 (2015)

untitled 16 (2015)

untitled 18 (2015)

untitled 18 (2015)

Black womanhood was demonized by white Southerners. Portrayed as disorderly, promiscuous, and violent, black women were afforded little respect. Many of the black female lynching victims challenged white supremacy, for example in labor disputes, or motivated by self-defense, such as when they were being sexually assaulted or their children were being attacked. A number of additional reasons included murdering a white person, attempted murder, arson, poisoning white people, stealing a Bible, train wrecking, having knowledge of a theft, singing too loudly or violating racial codes. And while the majority of black women who were lynched were poor, women from economically-successful families were murdered as well. Black women—as were often black men—were tortured and mutilated, and in some cases were raped before they were lynched. However, white women who were lynched were not often mutilated as were black women[5].

While most newspapers published detailed descriptions of alleged crimes committed by black men against white women, they rarely mentioned white men’s crimes against black or white women. White women were expected to live up to class and gender roles as imposed by white men, and if they threatened these or had relationships with black men, they had to suffer. “Prior to Emancipation, relationships between black men and poor white women were often tolerated, but after 1865, interracial relationships between black men and white women threatened the emergence of a segregated system” (Feimster 176). Ordinary white women had to live up to the standards of Southern womanhood or they would be punished. The number of white, mostly lower-class women who were lynched was much lower compared to black women, but they would often find themselves answering to nightriders, White Caps, regulators, or Klansmen, who disciplined these women: they were tarred and feathered, brutally whipped, violently warned to leave town, and sometimes lynched.

[1] Guzman, Jessie P., ed., 1952 Negro Yearbook (New York, 1952), pp. 275-279; numbers vary depending on source

[2] Equal Justice Initiative (2015) Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror. Report Summary. Montgomery, Alabama

[3] Feimster, Crystal N. (2009) Southern Horrors. Women and the Politics of Rape and Lynching. Harvard University Press: Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England: pp. 235-239.

[4] Numbers vary depending on source.

[5] Feimster, Crystal N. (2009) Southern Horrors. Women and the Politics of Rape and Lynching. Harvard University Press: Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England: pp. 158-185.

This project has been supported with grants from the Puffin Foundation and the UNC-Chapel Hill Department of Art & Art History.

At the Hands of Persons Unknown (2013-2015)

Sound piece

2:16 min

A record player plays a fictional monologue of Harriet Finch re-telling the story of her lynching on September 28, 1885 in Pittsboro, NC. Harriet Finch was lynched with her husband, Jerry Finch, and two other men, Lee Tyson and John Patisall. They were wrongfully convicted of murder. The monologue is read by Abigail Brooks Wright.

Installation with the names of the 169 women who were lynched between 1837 and 1965 (2018-19)

Laser Etchings on Plywood

Source: Feimster, Crystal N. (2009) Southern Horrors. Women and the Politics of Rape and Lynching. Harvard University Press: Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England: pp. 235-239.

![]() Installation with the projected, moving shadow of a lynching tree that is thought to evoke the aftermath of lychings (2019).

Installation with the projected, moving shadow of a lynching tree that is thought to evoke the aftermath of lychings (2019).

Projected photograph, laser-cut plywood, turntable, acrylic, screws

12"diameter, 18" height

The original photo was taken by Lawrence Beitler (courtesy of the Organization of American Historians). A crowd at the Marion, IN courthouse looks on following the lynching of Tom Shipp and Abe Smith on August 7, 1930. The black teenagers Tom Shipp, Abe Smith, and James Cameron were held in the Marion jail for the murder of Claude Deeter and rape of Mary Ball. (The rape charge was later dropped, as Ball retracted it.) Before they could stand trial, a mob comprised of white residents tore the young men from their cells and brutally beat them, mutilating and hanging Shipp and Smith from a tree on the courthouse lawn. Lynchers utilized shadows created by tree branches to obscure their identities. Cameron, the youngest of the three accused men, was ripped from his cell and nearly hanged before an unidentified woman in the crowd intervened, saying that he was not guilty. The lynchers intended to send a message to other African American residents, one which Marion NAACP leader Katherine “Flossie” Bailey scrambled to prevent.

You can watch a video about my solo show at the Center for Photography at Woodstock (CPW), NY in 2018 here. Listen to an interview with Antonio Flores-Lobos of Radio Kingston about my CPW show here. Listen to an interview with Filiz Cicek of WHFB Bloomington Community Radio about my solo show at Pictura Gallery in 2019 here.

Installation with the projected, moving shadow of a lynching tree that is thought to evoke the aftermath of lychings (2019).

Installation with the projected, moving shadow of a lynching tree that is thought to evoke the aftermath of lychings (2019). Projected photograph, laser-cut plywood, turntable, acrylic, screws

12"diameter, 18" height

The original photo was taken by Lawrence Beitler (courtesy of the Organization of American Historians). A crowd at the Marion, IN courthouse looks on following the lynching of Tom Shipp and Abe Smith on August 7, 1930. The black teenagers Tom Shipp, Abe Smith, and James Cameron were held in the Marion jail for the murder of Claude Deeter and rape of Mary Ball. (The rape charge was later dropped, as Ball retracted it.) Before they could stand trial, a mob comprised of white residents tore the young men from their cells and brutally beat them, mutilating and hanging Shipp and Smith from a tree on the courthouse lawn. Lynchers utilized shadows created by tree branches to obscure their identities. Cameron, the youngest of the three accused men, was ripped from his cell and nearly hanged before an unidentified woman in the crowd intervened, saying that he was not guilty. The lynchers intended to send a message to other African American residents, one which Marion NAACP leader Katherine “Flossie” Bailey scrambled to prevent.